Attacks on Educational Institutions

Executive summary

Cyberattacks against U.S. schools and colleges have escalated dramatically over the last few years. In the first half of 2025 ransomware incidents across the education sector increased 23 % year‑over‑year, with roughly 130 confirmed or suspected attacks and average ransom demands near US $556 k. A 2025 Center for Internet Security survey reported that 82 % of K‑12 schools experienced at least one cyber incident between July 2023 and December 2024, tallying 9 300 confirmed incidents across about 5 000 institutions. Emsisoft’s 2024 ransomware report counted 116 K‑12 school districts hit by ransomware, affecting an estimated 2 275 individual schools—an undercount given many attacks are never publicly disclosed. Universities have faced mass data exposures from supply‑chain breaches; the National Student Clearinghouse MOVEit hack alone leaked personal data from around 900 U.S. institutions. Recovery is costly: average remediation expenses reached US $3.76 M for K‑12 and US $4.02 M for higher education in 2024 (estimates from multiple sector studies). These numbers underscore the urgency for stronger cybersecurity controls, governance frameworks and transparency within the education sector.

Scope and methodology

This paper synthesizes publicly available statistics, government advisories, vendor reports and news articles published from 2023 through early September 2025. Key sources include K‑12 Dive, Emsisoft, SecurityWeek, Varonis, Jamf, UpGuard, Blackbaud, Saviynt and official notices from vendors like PowerSchool. Where data varied across reports, we state the range or note the uncertainty. The goal is to provide a concise yet comprehensive overview of current threats, notable incidents, underlying vulnerabilities and recommended controls for U.S. educational institutions.

Threat landscape

Ransomware as the dominant threat

Ransomware remains the single largest operational risk to schools and universities. The CIS found that human‑targeted attacks (phishing and social engineering) were the primary vector from July 2023 through December 2024, exceeding other techniques by about 45 %. In the first half of 2025, ransomware activity against education rose 23 % and ransom demands averaged US $556 k. Zscaler’s 2024 ransomware report observed 217 ransomware attacks on educational institutions between April 2023 and April 2024—a 35 % year‑over‑year increase—placing education among the top four targeted sectors. SonicWall later noted an 827 % spike in K‑12 ransomware attacks, while other analyses estimated an average downtime per incident of 1 600 days and US $2.8 M per breach.

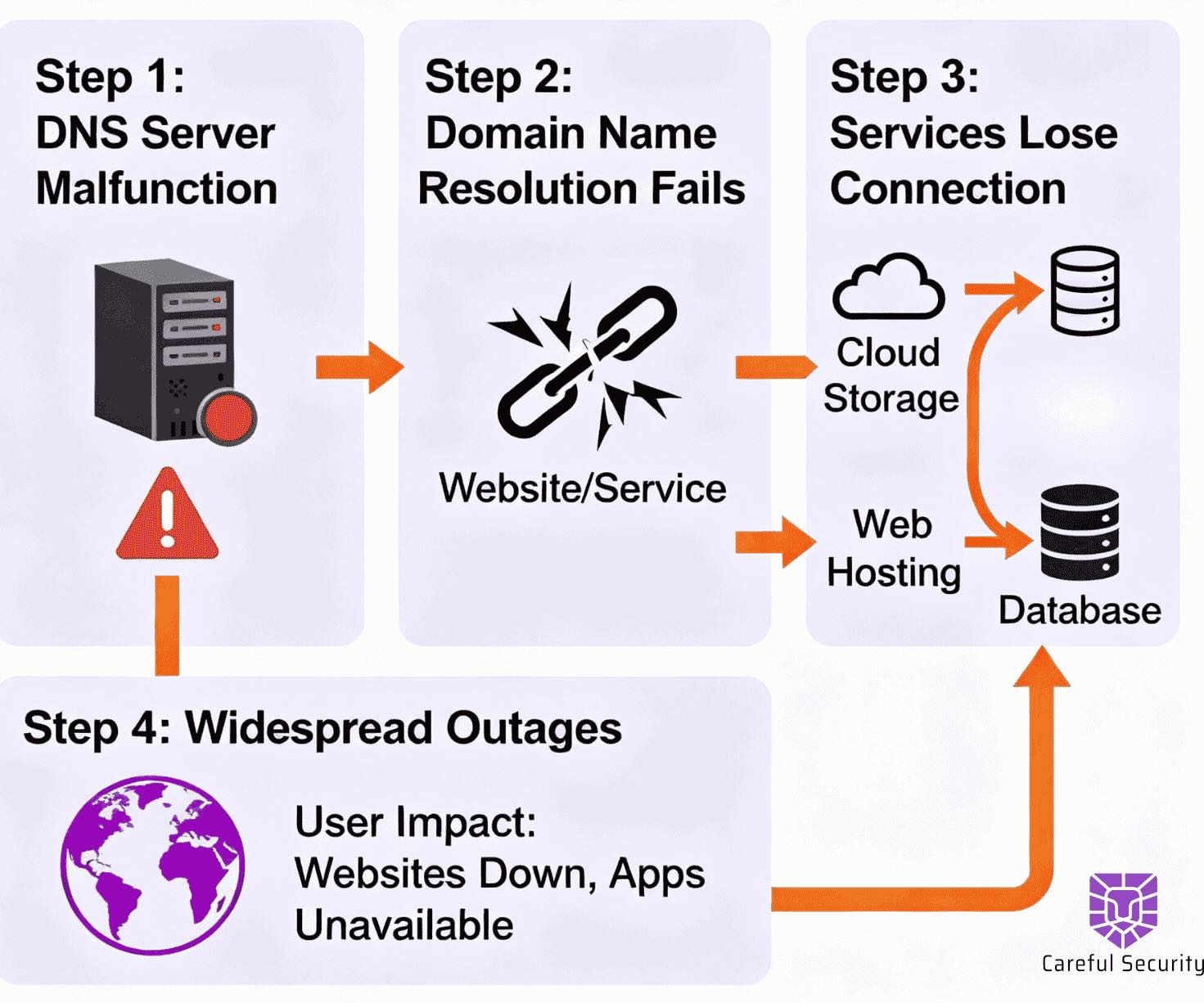

Supply‑chain and third‑party compromises

Schools increasingly rely on third‑party service providers for file transfer, student information systems and administrative functions. Breaches in these vendors often cascade across hundreds of institutions. The MOVEit file‑transfer vulnerability exploited in 2023–24 allowed attackers to exfiltrate data from the National Student Clearinghouse, impacting nearly 900 U.S. colleges and universities. In late 2024, an attack on PowerSchool’s customer support portal led to the theft of student names, contact details, birth dates, medical alerts and Social Security numbers from districts that used the platform. Because many districts share these platforms, such incidents highlight systemic risk and the difficulty of gauging the full scope of exposure.

Opportunistic actors and evolving tactics

Ransomware‑as‑a‑service crews such as LockBit, Medusa, Play and RansomHub frequently target education, taking advantage of limited budgets, broad attack surfaces and high dependency on digital services. Attack campaigns intensify around the start of school terms when disruption is most damaging. Government advisories in 2025 warned that Medusa and related groups employ double extortion—encrypting systems and threatening data leaks—to coerce payment. Sophisticated actors also pivot quickly between monetization methods; for example, the Hive ransomware gang reportedly extorted over US $100 million from U.S. school districts before being disrupted.

Costs, downtime and transparency issues

Recovery costs for ransomware incidents are rising. Sector studies reported mean remediation costs of about US $3.76 M for K‑12 and US $4.02 M for higher education in 2024, including incident response, forensics, legal fees, credit monitoring and downtime. Blackbaud’s analysis noted that ransom demands averaged US $1.5 M and that the United States accounted for 80 % of known educational ransomware incidents. Despite this, many districts underreport attacks to avoid reputational harm; some use outside counsel to manage notifications, resulting in delayed or limited disclosure. This lack of transparency hampers sector‑wide situational awareness and leaves parents and students uncertain about personal risks.

Common attack vectors

The following pathways are most frequently exploited in attacks on U.S. educational institutions:

- Credential phishing and social engineering: Students and staff are inundated with phishing emails and SMS messages that trick them into revealing login credentials. The CIS found that human‑targeted attacks were the dominant tactic during 2023–24. Attackers then use compromised accounts to move laterally through email, learning management systems and cloud storage.

- Unpatched systems and obsolete software: Many districts run out‑of‑date operating systems or end‑of‑life software. A 2025 UpGuard study discovered that 45 % of universities had at least one asset running end‑of‑life PHP and that 48 % used software with known exploited vulnerabilities. Legacy virtual private networks (VPNs) and unpatched edge devices remain common entry points.

- Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) exposures: UpGuard’s analysis found that 10 % of universities (23 % among the top 500) exposed RDP services to the internet. The FBI estimates that 70–80 % of ransomware infections are initiated via exposed RDP services.

- Weak identity and access management: Many schools lack enforced multifactor authentication. Saviynt reported that 60–70 % of breaches involve compromised credentials, emphasizing the need for privilege management and zero‑standing privilege (only enabling administrative access when needed).

- Third‑party vendor exposures: File transfer tools (e.g., MOVEit, Cleo), student information systems (PowerSchool, Infinite Campus) and other vendors become single points of failure; once compromised, attackers can access data from hundreds of districts. Supply‑chain attacks highlight the need for vendor risk assessments and contractual security requirements.

- Insider misconfigurations and misdeliveries: Non‑malicious errors—sending data to the wrong recipient or misconfiguring permissions—remain a significant source of data breaches. The K‑12 sector also struggles with insufficient staff training, making accidental disclosures more likely.

Notable incidents and case studies

- National Student Clearinghouse (MOVEit) breach (2023–24): A vulnerability in the MOVEit transfer software allowed attackers to download sensitive student data held by the NSC. The breach affected almost 900 U.S. colleges and universities, exposing names, Social Security numbers and other personal identifiers. The incident underscored the systemic risk of centralized educational service providers.

- PowerSchool support portal breach (December 2024): PowerSchool detected unauthorized access to its PowerSource customer support portal on 28 December 2024. Attackers exfiltrated names, contact information, birth dates, medical alerts and Social Security numbers from students whose districts used the service. The company offered credit monitoring but the breach highlighted how help‑desk tools can become entry points.

- Western Michigan University ransomware attack (2024): A 2024 attack caused a 13‑day network outage, forcing the university to shut down services and cancel classes.

- Minneapolis Public Schools breach (2023): Ransomware actors stole 300 000 files (including HR and payroll data) from Minneapolis Public Schools, later publishing them when the district refused to pay.

- Other high‑profile incidents: SonicWall and Varonis documented an 827 % surge in K‑12 ransomware attacks, more than doubling the number of affected districts from 2022 to 2023. Many smaller districts also fell victim to vendor breaches or targeted attacks, illustrating that no school is too small to be targeted.

Underlying vulnerabilities and sector challenges

Educational institutions face unique structural and resource constraints that exacerbate cyber risk:

- Resource limitations: School districts often lack dedicated cybersecurity personnel and rely on general IT staff; universities face competition for skilled professionals. The shortage of cybersecurity skills leads to gaps in threat detection and response, with surveys indicating that many small institutions have no one monitoring alerts overnight.

- Broad attack surfaces: Universities maintain numerous web domains and research networks. UpGuard found that the top 100 U.S. universities manage an average of 1 580 domains, while the top 500 manage 616 domains. Such sprawl creates more entry points and weak points for attackers.

- Legacy systems and technical debt: Budget constraints delay hardware refresh cycles and patch management. A large portion of educational institutions still run obsolete server software and operating systems.

- High‑value data: Schools hold personally identifiable information (PII), financial aid records, health accommodations and research intellectual property, making them lucrative targets for both monetary extortion and espionage.

- Seasonal timing: Cybercriminals time attacks around the start of terms, exam periods or admissions cycles, maximizing pressure on administrators to pay ransoms quickly.

- Third‑party reliance: Many districts outsource core functions to vendors; a breach in one system often cascades across hundreds of clients.

Regulatory and governance landscape

U.S. educational institutions must navigate a mosaic of federal, state and sector‑specific regulations:

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA): Governs the privacy of student education records and requires districts and universities to ensure confidentiality.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): Applies to universities that provide student health services, imposing strict requirements for protecting health information.

- Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLBA): Universities handling financial aid data must implement administrative, technical and physical safeguards; the act includes breach‑notification provisions.

- State breach‑notification laws: Each state sets notification timelines and defines personally identifiable information; districts must comply with the law of the state where affected individuals reside.

- Government Coordinating Council for Education Facilities: In 2024 the U.S. Department of Education established a council under the Department of Homeland Security to improve information sharing and resilience across the education subsector. The council complements the Multi‑State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS‑ISAC) and encourages adoption of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 and CISA’s cross‑sector performance goals.

- K12 SIX recommended controls: The K12 Security Information eXchange provides tailored controls for schools, emphasizing multi‑factor authentication, network segmentation, vendor management and incident response planning.

Impact on institutions and stakeholders

Cyber incidents have far‑reaching consequences beyond ransom demands:

- Financial toll: Costs include ransom payments, forensic investigations, legal and regulatory fines, credit monitoring, public relations and lost revenue. Studies estimate mean costs of US $3.76 M for K‑12 and US $4.02 M for higher education in 2024.

- Operational disruption: Schools often close facilities, cancel classes or revert to paper‑based processes for days or weeks. Western Michigan University’s 13‑day outage illustrates the magnitude of disruption.

- Data theft and identity fraud: Breaches compromise Social Security numbers, financial information and medical records, leading to long‑term identity‑theft risk for students and staff.

- Reputational damage and trust erosion: Parents and students lose confidence in institutions that delay disclosure or provide limited information about breaches. The psychological impact on teachers and administrators, who must manage crises, is also significant.

Recommended defensive measures

Improving cybersecurity in education requires a multi‑layered approach that balances technical controls, governance and culture. The following measures offer high impact for modest investment:

- Enforce phishing‑resistant MFA: Deploy multi‑factor authentication for all staff, students and third‑party vendors; disable legacy protocols; require step‑up authentication for high‑risk actions.

- Implement privileged access management (PAM): Adopt just‑in‑time access and eliminate shared administrator accounts; monitor and log privileged sessions; adopt zero‑standing privilege models.

- Segment networks: Separate student, administrative, research and vendor networks; use VLANs and firewall rules to restrict lateral movement and reduce ransomware spread.

- Update and patch promptly: Establish 7‑day patch deadlines for critical vulnerabilities and 30‑day deadlines for important ones; retire end‑of‑life software; regularly scan for known exploited vulnerabilities.

- Secure remote access: Disable unused RDP services and require VPNs with MFA; restrict IP ranges; use remote access gateways with strong authentication.

- Harden backups and disaster recovery: Maintain offline, immutable backups; test restoration regularly; document recovery playbooks for critical systems like learning management and student information systems.

- Enhance email and web filtering: Deploy DMARC/DKIM/SPF to prevent spoofing; use content filtering to block malicious attachments and URLs; deliver age‑appropriate cyber‑hygiene training to students and staff.

- Vet and monitor vendors: Perform due diligence on security practices of third‑party providers; contractually require security controls and timely breach notification; map data flows to understand exposure.

- Invest in continuous monitoring: Use managed detection and response services or build a 24×7 security operations center to triage alerts and respond quickly to intrusions.

- Establish incident response and transparency policies: Conduct ransomware tabletop exercises; prepare communication templates for stakeholders; balance legal considerations with the need to inform affected individuals promptly.

Cyber threats to U.S. educational institutions are persistent, complex and increasing. The combination of high‑value data, limited resources, expansive attack surfaces and heavy reliance on third‑party services makes schools and universities attractive targets. Statistics from 2023–25 show rising ransomware incidents, escalating ransom demands and wide‑ranging supply‑chain breaches. However, by implementing targeted controls—particularly strong identity management, network segmentation, patch management and vendor oversight—schools can substantially reduce their risk. Coordinated governance, transparent disclosure and continued investment in cybersecurity talent and awareness will be essential to protecting students, faculty and research in the years ahead.

Cybersecurity Leadership for Your Business

Get started with a free security assessment today.

.avif)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)